Most “green” IT procurement strategies fail because they focus narrowly on energy efficiency while ignoring the 80% of emissions generated before a device ever reaches your office.

- New Canadian legislation (Bills C-244 and C-59) transforms repairability from a voluntary preference into a legal procurement advantage.

- True sustainability requires shifting from purchasing disposable assets to managing circular resource loops through verified end-of-life accountability.

Recommendation: Audit your current RFP templates to prioritize repairability scores and Scope 3 accountability over generic carbon offset claims.

Checking an Energy Star box on a purchase order feels like progress, yet the device still ends up in a landfill after eighteen months when the battery dies or the screen cracks. This gap between intention and outcome plagues procurement officers tasked with greening supply chains while managing tight budgets and operational demands. The conventional approach focuses on operational energy use and carbon offsets, treating hardware as a consumable rather than a capital asset with a recoverable lifecycle.

But the emerging paradigm of Circularity-First Procurement offers a more rigorous framework. By leveraging Canada’s new Right to Repair legislation and adopting lifecycle costing methodologies, procurement professionals can transform IT acquisition from a linear drain on resources into a closed-loop system that delivers both ESG compliance and long-term cost containment. This requires looking past marketing claims to verify repairability infrastructure, Scope 3 accountability, and genuine end-of-life responsibility.

The following eight sections provide a strategic roadmap for implementing these principles within Canadian regulatory and supply chain contexts, covering everything from eco-label verification to the legal risks of greenwashing under Bill C-59.

To navigate these complexities systematically, this guide breaks down the procurement process into eight distinct strategic domains, each building toward a comprehensive circular asset management framework.

Table of Contents: Strategic Framework for Sustainable IT Acquisition

- EPEAT vs. Energy Star: Which Eco-Labels Actually Guarantee a Greener Product?

- Cost Per Year: Why a $2000 Laptop That Lasts 5 Years Is Greener Than Two $1000 Ones?

- iFixit Scores: Why You Should Check the Repairability Rating Before Buying Fleet Phones?

- End-of-Life: Does Your Vendor Guarantee Responsible Recycling When the Device Dies?

- Certified Refurbished: Is It Safe to Outfit a Sales Team With Pre-Owned Premium Devices?

- The Offset Trap: Why Buying Trees Isn’t Enough to Claim “Carbon Neutral” Anymore?

- Made in Canada: How Sourcing Local Artisan Goods Boosts Your Brand’s Reputation?

- The Right to Repair in Canada: How to Fix Your Gadgets Instead of Tossing Them?

EPEAT vs. Energy Star: Which Eco-Labels Actually Guarantee a Greener Product?

Energy Star certification has become the default baseline for “green” procurement, yet it addresses only one dimension of environmental impact: operational energy efficiency. While valuable for reducing electricity consumption during use, this label reveals nothing about hazardous material content, supply chain labor practices, or end-of-life recyclability. For procurement officers seeking genuine circularity-by-design, understanding the hierarchy of eco-labels becomes essential.

EPEAT (Electronic Product Environmental Assessment Tool) operates on a more comprehensive lifecycle model, evaluating criteria ranging from material selection and packaging to take-back programs and battery longevity. Unlike Energy Star’s self-certification model with periodic spot checks, EPEAT requires independent third-party verification and offers Bronze, Silver, and Gold tiers that reward progressive environmental leadership. However, even EPEAT addresses social criteria only as optional elements, leaving gaps in supply chain labor audits.

TCO Certified represents the most stringent standard available, mandating factory audits for ILO compliance, requiring minimum five-year product lifespans, and addressing repairability and upgradeability as compulsory criteria. In Canada, Shared Services Canada (SSC), which awards roughly $4 billion in IT contracts annually, requires devices purchased through the Workplace Technology Devices National Master Standing Offer to carry independent eco-label certification such as EPEAT or Energy Star, demonstrating how federal mandates can drive market transformation toward verified sustainability standards.

| Feature | Energy Star | EPEAT | TCO Certified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Energy efficiency during product use | Full lifecycle: materials, energy, end-of-life, packaging | Climate, substances, circularity, and supply chain (including labor) |

| ESG Pillar Addressed | E (Environmental – energy only) | E + partial S (some social criteria optional) | E + S + partial G (mandatory social audits, ILO compliance) |

| Verification Model | Self-certification with spot checks | Independent third-party verification (Bronze/Silver/Gold tiers) | All criteria mandatory; independent pre- and post-certification audits |

| Supply Chain Labor Audits | No | Optional criteria only | Yes – mandatory factory audits with corrective action plans |

| Canadian Government Use | Required in federal procurement | Required via Workplace Technology Devices NMSO | Used by global organizations; growing adoption in Canada |

| Circularity / Repairability | Not addressed | Addressed (take-back, battery programs) | Mandatory: min. 5-year product lifespan, repairability, upgradeability |

Selecting the appropriate certification tier depends on your organization’s specific ESG priorities, but procurement officers should recognize that Energy Star alone no longer suffices for comprehensive sustainability reporting.

Cost Per Year: Why a $2000 Laptop That Lasts 5 Years Is Greener Than Two $1000 Ones?

The procurement spreadsheet often favors the lower capital expenditure, creating a perverse incentive that prioritizes short-term budget relief over long-term value. A $1,000 laptop replaced every two years generates not only higher total cost of ownership but also significantly greater environmental impact than a $2,000 durable model maintained for five years. This calculation extends beyond simple purchase price to encompass deployment costs, IT support hours, data migration, and the hidden carbon debt of manufacturing.

The environmental mathematics proves stark: approximately 80% of total greenhouse gas emissions associated with an IT product occur before it reaches its first user, encompassing raw material extraction, component manufacturing, and global shipping logistics. By extending asset lifespan from two years to five, organizations effectively amortize that initial carbon debt across a longer service period, reducing annual Scope 3 emissions by more than half.

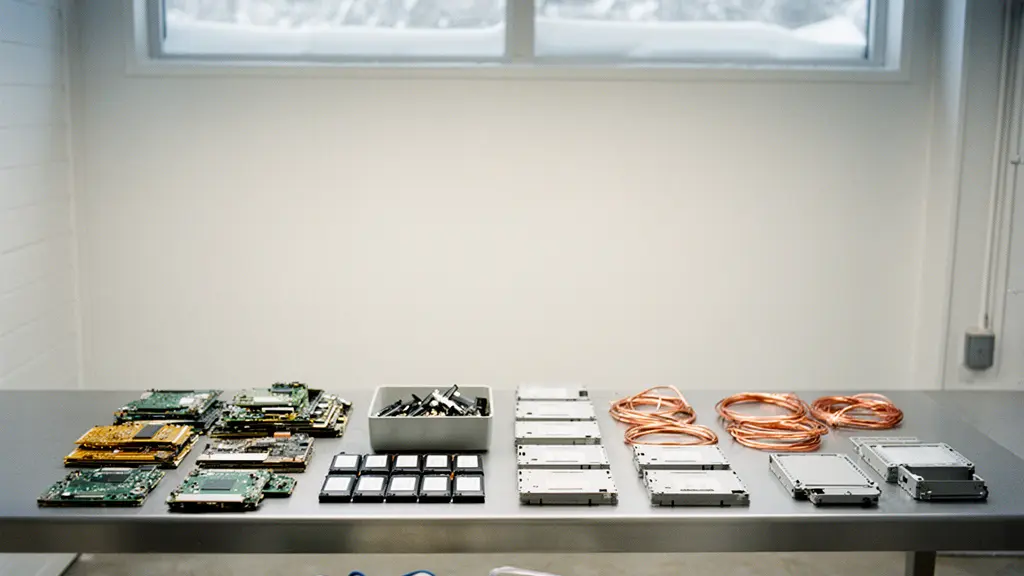

Visual inspection of hardware engineering reveals this divergence clearly. Premium devices typically feature modular components, standardized screws, and robust chassis construction that withstand thermal cycling and physical stress. Budget alternatives often rely on adhesive assemblies, proprietary fasteners, and plastic hinges engineered for planned obsolescence. For Canadian enterprises operating in diverse climates—from humid Atlantic offices to dry Prairie environments—this durability differential translates directly into asset lifespan extension and reduced total cost of ownership.

This approach requires securing capital budget approval for higher upfront costs, but the financial and environmental return on investment becomes undeniable across a standard depreciation cycle.

iFixit Scores: Why You Should Check the Repairability Rating Before Buying Fleet Phones?

Procurement specifications traditionally prioritize processor speed, memory capacity, and display resolution while ignoring a metric that determines actual device longevity: repairability. iFixit scores, ranging from one to ten, assess how easily a device can be disassembled, whether components are modular or glued, and if replacement parts remain available. In enterprise contexts where downtime translates directly to lost productivity, these scores offer crucial intelligence for fleet management.

For Canadian organizations, repairability carries additional significance given the extreme temperature variations that accelerate battery degradation. Field teams operating in sub-zero conditions require devices with easily replaceable batteries—a feature increasingly rare in modern sealed-unit smartphones. Recent legislative developments have transformed this from a preference into a strategic imperative. On November 7, 2024, Canada’s Parliament enacted Bills C-244 and C-294, amending the Copyright Act to permit circumvention of technological protection measures (TPMs) for repair purposes, meaning internal IT teams can now legally bypass digital locks to diagnose and maintain devices.

Procurement Roadmap: Integrating Repairability Into RFP Criteria

- Define a minimum repairability threshold (e.g., 7/10 iFixit score or equivalent) as a mandatory criterion in all IT procurement tenders.

- Require vendors to provide a battery replacement difficulty rating and cost estimate, critical for Canadian field teams working in sub-zero temperatures where battery degradation is accelerated.

- Add a clause requiring vendors to confirm compatibility with Bill C-244 — i.e., that no TPM prevents the purchaser or a third party from performing diagnosis, maintenance, or repair.

- Request vendor documentation on spare parts availability and guaranteed supply duration (minimum 5 years post-purchase) to mitigate northern supply chain delays.

- Score bids using a weighted matrix that balances repairability (20%), total cost of ownership (30%), eco-label certification (20%), and end-of-life recycling guarantee (30%).

This legal framework eliminates the previous uncertainty that forced companies into expensive OEM service contracts, creating new opportunities for in-house maintenance and third-party repair partnerships.

End-of-Life: Does Your Vendor Guarantee Responsible Recycling When the Device Dies?

The sustainability chain breaks at its weakest link: disposal. With over 60 million tonnes of e-waste generated globally each year, the final destination of decommissioned hardware represents a critical accountability gap in corporate ESG strategies. Procurement officers must verify that vendors provide concrete, verifiable end-of-life pathways rather than vague assurances of “eco-friendly disposal” that simply export waste to jurisdictions with weaker environmental protections.

In Canada, the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework requires electronics manufacturers to fund recycling programs, but procurement teams should demand specific documentation proving vendor participation in provincial stewardship programs such as EPRA/Recycle My Electronics. Data security adds another layer of complexity; simply wiping drives before disposal proves insufficient for compliance with PIPEDA and industry-specific privacy regulations. Organizations must require NAID Canada certified data destruction services that provide Certificates of Destruction for every batch, ensuring no sensitive information leaves Canadian soil on discarded storage devices.

Recent amendments to the Competition Act under Bill C-59, in force since June 20, 2024, further elevate the stakes. Greenwashing liability now attaches to unsubstantiated environmental claims, meaning vague recycling promises expose organizations to regulatory scrutiny. Procurement contracts must specify that recycling claims require adequate and proper evidence per internationally recognized methodology, with archived documentation serving as tangible ESG assets for annual Corporate Social Responsibility reporting.

Vendor Audit Checklist: Verifying Responsible End-of-Life Management

- Verify vendor partnership with EPRA/Recycle My Electronics — request documentation proving membership in the official provincial stewardship program for the province(s) where your offices operate.

- Demand NAID Canada certified data destruction services to ensure compliance with PIPEDA and that no personal data leaves Canadian soil on discarded hard drives; request a Certificate of Destruction for every batch.

- Under Canada’s new greenwashing provisions (Bill C-59, in force June 20, 2024), ensure your vendor’s recycling claims are substantiated with adequate and proper evidence per internationally recognized methodology — vague claims like ‘eco-friendly disposal’ are now a legal liability.

- Archive all Certificates of Destruction and recycling receipts as tangible ESG assets for your annual Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) report and potential audit by the Competition Bureau.

This proactive approach transforms disposal from an afterthought into a governed process that protects both environmental integrity and corporate reputation.

Certified Refurbished: Is It Safe to Outfit a Sales Team With Pre-Owned Premium Devices?

The stigma surrounding refurbished enterprise equipment persists despite significant improvements in certification standards and quality assurance. For client-facing sales teams, device appearance directly influences brand perception, making the “used” label particularly concerning. However, Grade A refurbished devices—defined as units in near-mint cosmetic condition with minimal or no visible wear—offer performance parity with new equipment while delivering substantial environmental benefits through circularity-by-design.

The key lies in sourcing through authorized channels. Microsoft Authorized Refurbishers (MAR) and equivalent OEM-approved partners based in Canada, such as Bauer Systems, provide domestic warranty processing that eliminates cross-border friction and ensures compliance with Canadian consumer protection laws. These devices undergo comprehensive testing, component replacement, and cosmetic restoration to meet stringent standards. While refurbished units do not carry new EPEAT certifications, the act of extending a device’s lifecycle aligns directly with circularity criteria and TCO Certified’s emphasis on minimum five-year product lifespans, allowing procurement teams to document these purchases as verified circularity initiatives in ESG reports.

Despite these advantages, Canadian public sector purchases account for 13.3% (~$200 billion CAD) of Canada’s GDP, yet the vast majority of RFPs do not consider sustainability as a key factor. This gap represents a missed opportunity, particularly given that premium refurbished business laptops often outperform new consumer-grade devices in reliability metrics. For sales teams, the professional appearance of a high-end refurbished ThinkPad or Latitude typically exceeds that of a new entry-level model, offering both functional superiority and environmental credibility.

The financial savings realized through strategic refurbishment can be redirected toward extended warranty programs or internal repair capability building.

The Offset Trap: Why Buying Trees Isn’t Enough to Claim “Carbon Neutral” Anymore?

Carbon offsetting has long served as a convenient mechanism for declaring IT procurement “carbon neutral” without addressing underlying consumption patterns. By purchasing credits funding reforestation projects or renewable energy installations, organizations claimed environmental equivalence while continuing to replace devices on aggressive two-year cycles. This approach faces increasing legal and scientific scrutiny, particularly regarding the permanence of forest carbon sinks and the accuracy of baseline emissions calculations.

Canada’s legislative landscape has shifted decisively against such claims. Bill C-59, receiving Royal Assent on June 20, 2024, amended the Competition Act to explicitly target greenwashing. Under the revamped section 74.01(1), any environmental benefit claim—including carbon neutrality assertions based on offsets—must now be substantiated with adequate and proper testing based on internationally recognized methodology. Beginning June 20, 2025, private parties can seek leave from the Competition Tribunal to commence actions under these provisions, dramatically increasing enforcement risk for unsubstantiated claims.

With the new provisions, businesses are now required to make sure that there is an adequate and proper basis prior to making certain environmental claims.

– Competition Bureau Canada, Environmental claims and the Competition Act — Official Bureau Guidance

For procurement officers, this regulatory evolution necessitates a fundamental strategic pivot. Rather than purchasing offsets to compensate for high-turnover hardware strategies, organizations must prioritize Scope 3 accountability through durability, repairability, and responsible end-of-life management. Genuine carbon reduction—achieved by extending device lifecycles and minimizing manufacturing demand—offers defensible environmental benefits that withstand regulatory scrutiny, unlike purchased neutrality that disappears the moment a forest fire releases sequestered carbon back into the atmosphere.

The transition from offsetting to actual reduction represents the next maturity level for sustainable procurement.

Made in Canada: How Sourcing Local Artisan Goods Boosts Your Brand’s Reputation?

While “Made in Canada” evokes images of handcrafted goods and artisanal manufacturing, the strategic value of local sourcing extends far beyond boutique corporate gifts. In IT procurement, localism manifests through repair networks, refurbishment centers, and component suppliers that reduce the carbon intensity of supply chains. More than 50% of global CO2 emissions are concentrated in the supply chains of just eight industries, highlighting the environmental imperative of shortening logistical distances and regionalizing maintenance infrastructure.

For Canadian procurement officers, local sourcing creates resilience against global supply chain disruptions while supporting domestic circular economy development. Rather than shipping defective devices to international service centers, organizations can leverage local Repair Cafés and authorized service providers—active in Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, and Ottawa—for maintenance that keeps assets in service longer. This approach proves particularly valuable for remote and northern operations where international shipping delays can render devices unusable for weeks.

Beyond logistics, local procurement supports the repairability infrastructure necessary for circularity. When procurement budgets flow to Canadian-owned refurbishment operations and component distributors, they strengthen the domestic ecosystem required to maintain extended lifecycles. This creates a virtuous cycle where procurement decisions enable the local capacity that makes future sustainable procurement viable, embedding social value within environmental strategy.

The reputational benefits of local sourcing complement the measurable environmental advantages, creating dual value for stakeholder reporting.

Key Takeaways

- Prioritize repairability scores (iFixit 7+) and TCO Certified standards over basic Energy Star compliance to ensure true lifecycle sustainability.

- Leverage Bills C-244 and C-59 to transform repairability from a preference into a legal procurement advantage while avoiding greenwashing liability.

- Calculate total cost of ownership using five-year depreciation cycles that account for the 80% of emissions generated during manufacturing, not just operational use.

The Right to Repair in Canada: How to Fix Your Gadgets Instead of Tossing Them?

The culmination of sustainable IT procurement strategy lies in operationalizing the legal right to maintain and repair assets internally. Bill C-244, passed unanimously by the House of Commons, amends the Copyright Act to specify that prohibitions on circumventing technological protection measures (TPMs) do not apply when maintaining or repairing products. Complemented by Bill C-294 enacted simultaneously on November 7, 2024, this legislation eliminates the legal uncertainty that previously forced Canadian businesses into expensive OEM service contracts or premature device replacement.

The practical implications prove transformative for enterprise IT management. Internal teams may now legally bypass digital locks to diagnose software issues, replace batteries in sealed devices, and upgrade storage or memory components without voiding warranties or facing copyright liability. Members of Parliament specifically noted the positive impact for rural and northern Canadians with limited access to authorized repair facilities, acknowledging that electronics waste is globally among the fastest-growing types of waste, increasing at a rate of 3% to 4% each year.

Implementation Plan: Operationalizing Right to Repair in Your Organization

- Update your IT Acceptable Use Policy to explicitly authorize internal technicians and approved third-party repair shops to circumvent TPMs for diagnosis, maintenance, and repair — as now legally permitted under the amended Copyright Act (Bills C-244 and C-294, enacted November 7, 2024).

- Build a local spare parts inventory for your most common fleet devices (batteries, screens, charging ports) — consider CRA Class 50 treatment at 55% CCA for parts classified as computer equipment, and stock strategically to mitigate supply chain delays common in northern and remote Canadian locations.

- Explore community repair partnerships — connect with local Repair Cafés (active in cities like Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, and Ottawa) for employee engagement days that combine device maintenance with team-building and sustainability skill-sharing.

This legislative framework positions procurement officers as circular economy architects rather than mere purchasers. By selecting repairable hardware, establishing local parts inventories, and training internal teams, organizations can decouple their operations from the linear consumption model. The result extends beyond cost savings to encompass true asset lifespan extension and the elimination of unnecessary e-waste generation.

Begin auditing your current device portfolio against iFixit repairability scores immediately, and update RFP templates to mandate TPM compatibility with Canadian repair rights before your next procurement cycle.

Frequently Asked Questions About Certified Refurbished IT for Enterprise Use in Canada

What does ‘Grade A’ refurbished mean for client-facing sales staff?

Grade A refurbished devices are in near-mint cosmetic condition with minimal or no visible wear — no scratches, dents, or discoloration. For sales teams who represent your brand in meetings, Grade A ensures the device projects professionalism equal to new equipment.

How do I avoid cross-border warranty friction when sourcing refurbished in Canada?

Prioritize purchasing from Microsoft Authorized Refurbishers or equivalent OEM-approved partners based in Canada (e.g., Bauer Systems). This ensures warranty claims are processed domestically, eliminates import duties, and guarantees compliance with Canadian consumer protection laws.

Can refurbished devices meet EPEAT or other eco-label standards?

While refurbished devices do not carry new EPEAT certifications, the act of extending a device’s lifecycle aligns directly with EPEAT’s circularity criteria and TCO Certified’s emphasis on minimum 5-year product lifespans. Procurement of refurbished devices can be documented as a circularity initiative in ESG reports.